Umegahata, Kyoto. This area was once home to a concentration of Japan’s leading natural whetstone mines. Nakayama, Okudono, Kitayama, Beniyama, and Mukoda – these names are still talked about among grinding stone enthusiasts today, but there is one mine in particular that is particularly mysterious and about which little information is available. But there is one mine that is even more mysterious and about which little information is available: Inoshiri Mountain. To tell the truth, I did not know of the existence of the Inoshiri Mine. I quote from the explanation of Mr. Tanaka, the director of the Natural Grinding Wheel Museum, who was kind enough to help me.

Inoshiri Mountain is a grinding stone mined in Umegabatake, Kyoto. The vein starts from Mukoda and is connected to Nakayama, Kita-Nakayama, Inoshiri Mountain, and Beniyama. The mine is now closed and the mining pit is buried. It is a rare stone that is hard to find in this size.

Table Of Contents

- Where is Mt. Inojiri?

- Appearance of Mt. Inajiriyama whetstone ─ Toro bark, yellowish brown color, silky flow pattern

- Actual sharpening – No.1000, Aosu-zuba plate, and then to Inoshiri Mountain

- Evaluation of the polished surface – a “cloudy mirror surface” texture

- Summary of the character of the Inoshiri Mountain Grindstone

- Estimation of stratigraphic classification – door front or ceiling door front?

- In Summary – A visionary grinding stone that must be appreciated now.

Where is Mt. Inojiri?

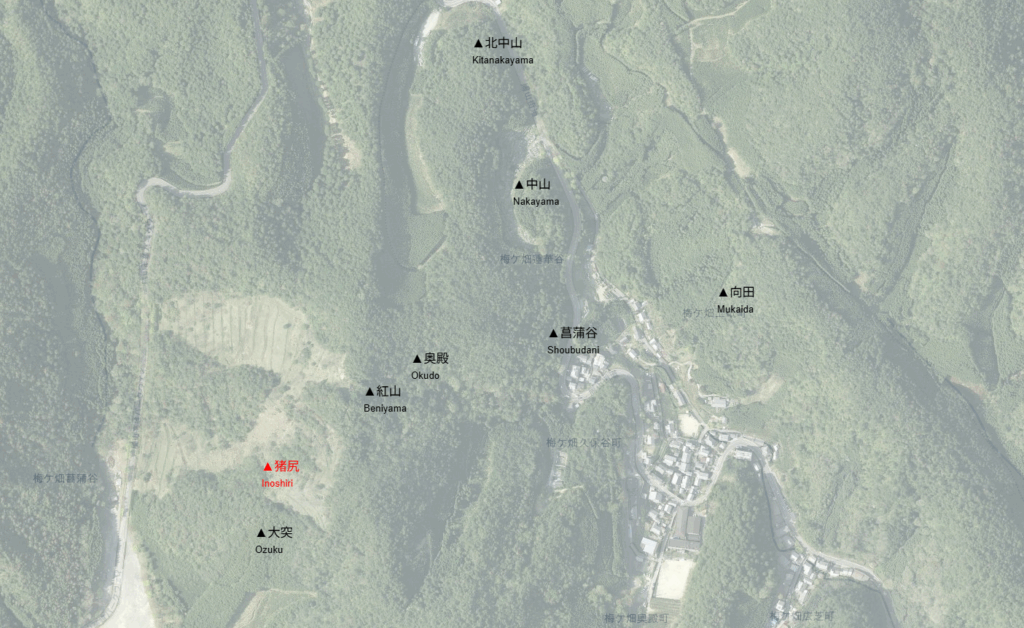

As for the veins, starting from Mukoda, they are connected to Nakayama, Kita-Nakayama, Inoshiri Mountain, and Beniyama.

Since I was not sure of the location of the mines, I looked up the latitude and longitude of each mine based on Director Tanaka’s words, albeit roughly, and used Python to embed the map in GSI’s map and output the map in HTML. I put Mt. Inojiri in red.

Inajiriyama is located just south of the Nakayama Mine and is part of a high-quality sedimentary formation that is considered to be “Honkuchi-nari”, which as a mineral vein extends to Nakayama, Kita-Nakayama, Inajiriyama, and Beniyama. In other words, it is geologically in the same family as the fine-grained layers represented by Sobita, Tozen, and Hachimai.

Appearance of Mt. Inajiriyama whetstone ─ Toro bark, yellowish brown color, silky flow pattern

If I were the first holder, I would not have written this in oil-based ink. It is not a hobby of mine, but lately, even the Showa-era smelling letters are starting to look cute.

The surface is light ochre in color, with a slight reddish tinge visible. There are no noticeable nests or threads, indicating that the surface is filled with homogeneous abrasive grains. The polished surface has a silky cloudy pattern running along the surface, revealing a beautiful ground surface that shimmers faintly when exposed to light. The reddish-brown toro-bark remains firmly in place on the sides and back surfaces, and its texture is very similar to that of Nakayama’s Tozen line of whetstones. In particular, I got the impression that it is similar to the whetstone called “Tomei Tozen Shikimono”.

Actual sharpening – No.1000, Aosu-zuba plate, and then to Inoshiri Mountain

In this case, the following order was adopted as the sharpening process. The knife used is “Drunken Heart’s Funagyo” and the steel material is Shiragami No. 2 (White No. 2).

- Blade blackening No. 1000 (molding and scratch removal)

- Blue nest board (medium finish) at Maruoyama

- Inajiriyama Grinding Wheel (final finishing)

Blade mastermind 1000 to make a rough shape.

A blue nest board from Maruoyama erases the scratches on the 1000. It is a little dark, but has a nice cloudiness. Aosuita is really my favorite whetstone.

Final finishing with Inajiriyama whetstone. It is hard to see in the photo, but it is clouded brighter than the blue nest board. It is not like a mirror surface, but I like the bright cloudy (almost semi-mirror surface) finish.

When water is sprinkled on the Inajiriyama whetstone, it instantly blends with the water and a slight shade of gray appears on the surface of the whetstone. When the blade is lightly stroked, it is quickly absorbed by the blade, but you feel almost no resistance. Whenever you slide the blade, you feel as if the abrasive grains are quietly stroking the steel and metal. Very little grit is produced. More precisely, it is not too much. It is as if an extremely thin layer of high quality mud floats on the surface of the blade and is transferred to the blade as a cloudy film.

Evaluation of the polished surface – a “cloudy mirror surface” texture

The image of the blade edge shows that the fine scratches left by the aozu plate have been softly suppressed by the Inoshiriyama whetstone. The shade of cloudiness spreads out like a gradation toward the center of the blade edge, expressing the “quiet refinement” that can only be achieved with a natural whetstone. This finish is in a different realm from that of an artificial whetstone, and is particularly well suited to steel materials such as Shiragami No. 2. This characteristic, in which the abrasive grains do not shave the steel but rather “stroke” it, makes it an ideal finishing stone for the final stage of bringing a blade to life.

First of all, the base metal is dull and light, showing cloudy reflections like the surface of a lake with morning mist. It is by no means a mirror surface. But what is there is a “quiet texture” that can only be obtained with a natural whetstone. And the fine scratches that were left by the aosu-plate have almost disappeared, leaving a homogeneous cloudiness and well-defined lines from the cutting edge to the peak side. The edge is now firmly in place around the small blade, leaving a hint of a crisp paper cut, and beautifully finished. This sharpening skin conditioning is similar to the slightly harder Tozen among the whetstones I have. The mud does not go out of control, the particles are very fine, and it has excellent power to stroke and condition the surface. It can be said to be a whetstone that has “the rationale of finishing” – it evens out rough surfaces and leads the blade line straight.

Summary of the character of the Inoshiri Mountain Grindstone

- Grain size: Super-finishing equivalent (#10000-12000 equivalent)

- Mud Appearance: very discreet, ultra-fine finishing mud

- Sharpenability: Smooth and soft touch, and the surface does not collapse.

- Recommended steel materials: White 1, White 2, Blue paper type, SG2, etc. All medium and high hardness blades

- Finish tendency: Cloudy to semi-glossy/not too mirror-like

Estimation of stratigraphic classification – door front or ceiling door front?

Overall, from the appearance and performance, the texture of the skin, and the way the grit mud appears, this whetstone is considered to be very close to the “Hontomae – Toujyo-tomae” layer of Honkuchi-nari. It does not have “a lot of mud” or “softness” as seen in Zuita, Gousa, and Renge, but rather, it has a grain size and hardness that seems to stop right at the finishing stage. Furthermore, the back skin is very similar to Nakayama’s toro bark, and has strong characteristics of honkuchi-nari. Personally, I have the impression that it is similar to the finish-specific type of medium-hard Tozen, especially the “Ceiling Tozen Color” and other types of Tozen.

In Summary – A visionary grinding stone that must be appreciated now.

Inojiriyama – few sharpeners may have heard of this name.

But its capabilities are obvious. The fineness of the particles, the beauty of the finish, the controllability of the sharpening, and the ease of use. In all of these, this is a first-class product. A mine that will never be mined again. A place of production where no information remains. Because it is like a “fading memory,” I want to sharpen this whetstone, record it, and pass it on.

Sharpeners will touch the whetstone, be amazed at its history and quality, and pass it on. We believe that this is the way to bring the quiet name of Mt.